What if we started.. not with long-established theories, but with humanity’s long-term goals, and then sought out the thinking that would enable us to achieve them?

Kate Raworth

The National Energy Code for Buildings has been upon us for a few years now, and is giving the construction industry a not-insignificant nudge in the direction of energy efficiency. It’s a good start, although its full benefits may only be felt over a somewhat glacial timeframe.

That slow pace of change is likely on purpose: change too much, too fast, and you risk upsetting the economic applecart, or there is enough pushback from industry or from the public that the project stalls entirely. That’s a serious consideration, and is kind of baked into human nature.

I can’t help thinking, though, that as good as the NECB is, it’s not nearly enough. The apple cart is well on its way to being tipped over by forces beyond our control, and an entirely new set of problems is headed our way.

Let’s take this from another angle for a moment, and pose a question: “What qualities does a building need to have, to be considered ‘good’, in Canada?” And a second question, “Will anything about those qualities need to change as the second half of this century approaches?” (There’s a third question, but that comes later.)

Here are some of the commonly looked-for qualities of a Canadian building. These may be the same in name in other parts of the world, but different in practical application depending on climatic, cultural and other factors of the locality.

[This list contains drop down content – make sure to click open to read it all!]

1. Stay warm in winter.

No surprise here, much of a year’s weather is on the chilly side, and Canadians are pretty good at keeping buildings warm. Moderately well-insulated buildings and a cheap fuel source make for an acceptable solution, for now. Zoom ahead a couple decades, though, and things begin to look a bit different:

- Fuel costs won’t be cheaper. I don’t recall ever seeing natural gas or electric rates go any direction but up.

- The fossil fuels that are the basis of most of our current heating energy are, no matter how you slice it, a finite resource. At some point there is simply going to be less to go around, and prices will go up more.

- The massive infrastructure that delivers the gas and electricity to our buildings is itself dependent for its continued functioning on a highly complex global supply chain. If the last two years have taught us nothing else, we should at least have an inkling of the disruptability of these intricate systems.

So, our twenty-year-from-now selves might be thinking that buildings that can be kept warm with a bare minimum of external energy input would be a cracking good idea. Better yet if that modicum of energy is reliably available from sources not vulnerable to sudden and widespread failure.

2. Stay cool in summer.

In my part of the country, a few hot summer nights are a nice change from the normal weather, and the sweaty indoor discomfort of our bungalow is easily enough managed. Some of the neighbours even have small air conditioners. However, summer heat gain is a much bigger deal in other regions of Canada, and as we have seen this problem is only going to increase. In most parts of our country, keeping buildings cool in summer is going to be at least as big a problem as keeping them warm in winter. Cranking up the A/C isn’t really a solution either, for various reasons including affordability (see point 1 above). Our twenty-year-from-now selves will be as familiar with the wet-bulb temperature report (and the lethal “wet-bulb-35C”) as we are with wind chill, and having reliably cool indoor spaces available will be a top concern.

3. Don’t lose roof in wind.

One of the features of a warming climate include increasing intensity and frequency of storms. The smart money will be on wind-resistive designs for buildings.

4. Don’t burn down (or take the neighbours with it).

This is a vital concern of our present time, of course, and great advances have been made in fire-resistive building methods, resulting in declining rates of catastrophic fires in new buildings. Residential sprinkler systems have also proven their worth and hopefully will become ubiquitous as range hoods and doorbells. So many improvements have been made that make our homes and workplaces safer from fire.

And yet. My own town’s water source is a large shallow lake, which was so depleted in the dry 1930’s that farmers cut hay across the entire width of it. Should that situation recur (and there is no reason to think that it will not), we will be in for a major overhaul of some infrastructure. The water supply of many communities is vulnerable to some extent from drought, and some are already experiencing this acutely.

The long term trends, we’re told, include increasingly hot and dry conditions across much of continental North America. The implications of this are many, but one that jumps out is that at some point, copious amounts of water for firefighting may not be available, and Murphy will ensure that that will also be the day that a drought-fueled wildfire threatens your suburb, or a massive structure fire threatens to rip through a housing development.

The fire-resistive buildings of today will be the survivors in years to come.

5. Be durable (or at least fixable).

Not to belabour this point, but it needs to be acknowledged that the life expectancy of modern buildings is short, especially compared to the centuries-old and still-functioning buildings found in other parts of the world. A lot has to do with the way materials react to the stresses of cold, heat, moisture and chemical processes. That most apparently-permanent of materials, concrete, is often crumbling within 50 years, especially if reinforced with steel in the conventional manner. Adhesives, engineered wood, and the synthetic materials used in our buildings all deteriorate predictably.

So, building things that “last forever” is likely unrealistic. Maybe what our future selves would like from us is buildings that can be repaired affordably once those original components have done their time. Another strategy is to use materials that can, in future, be used again for other purposes, rather than going straight to the landfill.

6. Provide a healthy indoor environment.

Heat waves and declining outdoor air quality are likely to drive us indoors more often in the future, so providing healthy indoor environments will be even more critical than at present, when a great deal of attention is already being paid to the subject. Some of the challenges that won’t be getting smaller include:

- Mould. This has been the plague of energy-efficient buildings since the 1970’s. Tight building envelopes are great at creating perfect habitats for hungry microbes, and the results are devastating. Our push for ever-more-efficient buildings means that we need to become really good at designing for non-mustiness.

- Fresh air. Fresh air is of vital importance to human health, and we can no longer count on simply bringing in outdoor air. That outdoor air, too often now and probably increasingly so in future, is polluted with smoke from distant massive wildfires at the very time that we are indoors escaping the summer heat wave. The development of ingenious filtering solutions is sure to be a growth industry.

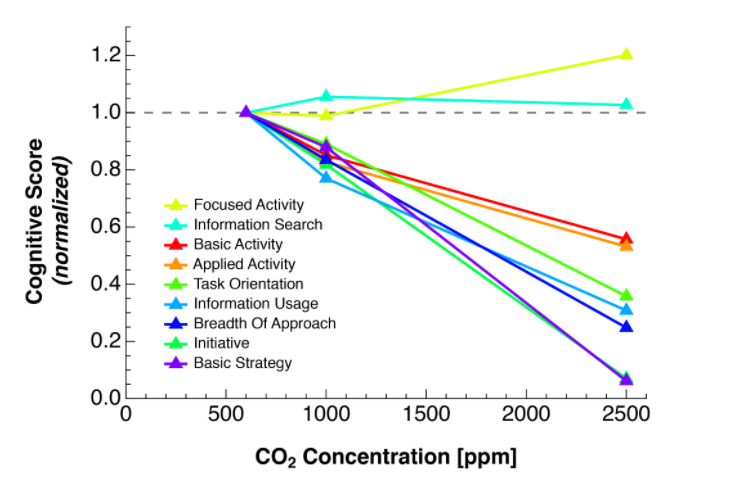

- CO2. It may surprise you to know that indoor levels of carbon dioxide are often substantially higher than they are outside. Studies show that indoor CO2, particularly in winter, can soar to levels well in excess of 1000ppm in many dwellings. As un-alarming as this may sound, it is also worth noting that the human brain starts to be affected by prolonged exposure to concentrations above 500ppm. Our neurology is well adapted to the 300ppm atmospheric concentration that was the planet’s baseline for all of our species’s existence. Currently, the atmospheric CO2 is closing in on 420ppm, and is expected to reach levels of 800 or more in the second half of this century.

It is a sobering thought that right now, in 2022, we are at the peak of our mental abilities, and thanks to CO2 we are not, collectively, going to get any smarter. Quite the opposite, it appears.

What this means for buildings is a stunning role-reversal: rather than going outdoors for the benefits of fresh air, we will be forced indoors to escape increasingly unhealthy atmospheric conditions outside. Those indoor spaces, then, had better be providing us with the low CO2 levels that our brains need. (Otherwise we will forget supper on the stove and burn the house down.)

Plants come to mind as a ready-made solution, although providing the space, lighting and humidity necessary is a challenge requiring great cognitive functioning to solve. Then there’s that mould issue again. There is a bright future ahead for the successful residential greenhouse designer-builder.

- Water. A civil engineer and I enjoyed friendly arguments about whether the municipal distribution system’s principal purpose was to supply water for domestic consumption or for firefighting. We never agreed, but the beer was good.

There are a few more serious questions that need asking: Why do we flush potable water down our toilets? In the face of possible prolonged drought, why do we insist on making all the precipitation run off and away, rather than trying to hold onto it for future considerations? How sustainable, in the long run, is the maintenance of all that buried pipe?

- Resilient. Whatever the systems developed to keep our indoor air of a suitable quality, they had better be dependable, and protected in some measure from the power outages, supply chain disruptions and other threats.

7. Be a suitable size for its purpose.

Our twenty-year-from-now selves may come to resent the luxurious floor plans that we are so fond of at present. Large single-family homes are already the privilege of the well-heeled, in the larger cities at least. This mode of housing might just become a relic of the past.

To paraphrase Tolstoy: “How much space does a person really need?” Our future selves might answer thusly: “Just enough space for daily necessities, and small enough that we can afford to heat it”. Our future lifestyles, and the buildings we consider desirable, might be a lot smaller and quieter than we are used to. That could be a good thing. Perhaps the resources saved could be put into better public amenities, for the benefit of all.

8. Be suitable for its site.

The current residential development model is pretty brutal when you think of it: Select a random site, impose an arbitrary arrangement of lots and streets, re-form the shape of the land to fit the plan, plunk down uniform houses in a uniform pattern, and send for the smiling realtors. Lost forever are any opportunity to make use of existing natural features, to shape the neighbourhood around the existing landscape, or to place the house within its site in a manner that takes the best advantage of sunlight, connects the house to its yard, and other nuances that can make all the difference to how liveable the place really is. Just sayin’.

9. Be affordable.

The pandemic years brought us soaring material costs and construction-stopping shortages. Home ownership is increasingly out of range for many. Not having a home at all is increasingly probable for a growing number of our fellow citizens. Our society is still affluent, overall, and many expect that it will continue to be so. There is also a pretty good chance that it won’t.

The point: Let’s not set our future selves up for expensive repairs, retrofits or rebuilding that we possibly won’t have the means to accomplish at that time. Right now may be our best moment to make the future financially feasible.

The other point: Let’s stop leaving people behind. It will be all very well for the gilded few to sit in their plant-filled geo-bubbles, making reservations at the Restaurant at the End of Civilization (1). If the mass of humanity is left to wither outside those exclusive bubbles, then we will have no right to call ourselves any sort of just or civilized society. We can’t leave it to our future selves to sort this out, either. We’re the smart ones, remember.

Here’s the third question: “If buildings will need to be significantly better in a couple decades’ time, why on earth don’t we build them that way now?” This should be a burning question of our times, and the answers involve a bit of a renovation to our perspectives, priorities and habits of thinking.

We are not, as a species, very good at connecting our present with our future, especially when that future holds some fundamental challenges to the way we like to think about ourselves. We’re more responsive to urgent immediate problems than to a slow-moving major threat on the horizon. That asteroid won’t really worry us until it is about to land on us before breakfast tomorrow. That’s our challenge: to shift our focus farther ahead, figure out what we will need in two, three, five decade’s time, and start to work on those things now. Our future selves would marvel in gratitude at our wonderful foresight. Our inner ancient brains will grumble, but they’ll survive.

So what, you have been wondering, does this have to do with the role of the building official? Are we not, after all, just functionaries, ticking boxes in the permit process, following the script set out for us, ensuring compliance wherever we go? I think we have a lot more to offer than that. We are in a unique position of influence, and have the opportunity to ask the questions that may spark amazing new ideas and innovations that would otherwise go unrealized.

It is easy to put up roadblocks, for creativity and invention to crash into and die. That has been the experience in far too many municipal offices. I think we should instead try to act as trail guides, doing our best to connect the most innovative builders with the knowledge and the resources they will need to have the best chance of success. Too many alternative or experimental projects have been carried out by well-intentioned people and ended in failure. Positive interactions with the local building standards officials can turn such projects into learning experiences, and sources of inspiration for further innovation.

It is encouraging to think that some aspect of our work will have a lasting and meaningful impact, beyond the dry text of our job descriptions. Perhaps the ideas discussed above will inspire you to take a new look at our vocation, and its potential to be a powerful force for change.

Suggested Reading

Neil’s Picks:

- Rebuilding Earth, Designing Ecoconscious Habitats for Humans, Teresa Coady

- Effects of CO2 on decision-making abilities of humans (one of many)

- Donut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Kate Raworth

- The Long Descent, Greer

- Residential indoor air quality guidelines, Health Canada

- Our World In Data

Kilo’s Picks:

- Rebuilding Earth, Designing Ecoconscious Habitats for Humans, Teresa Coady

- Strong Towns

- The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs

Notes: (1) Readers of Douglas Adams will understand.