A Living Document

In Canada, the two main Codes that regulate fire and life safety within buildings are the National Building Code and National Fire Code, first published in 1941 and 1963 respectively. The Building Code guides fire safe design and fire prevention in the design and construction of buildings whereas the Fire Code is used to control fire prevention on a continuing basis after the building has been constructed. Both are equally important and work in unison to prevent fires and promote safe buildings for the public interest. They are living documents that are continuously evolving with adaptations that respond to new knowledge, technologies, and trends.

Codes like these are commonplace in most modern societies – they promote a standard level of expectations by the public on building safety and how buildings should perform. Many of today’s Codes are expanding to encompass energy efficiency, accessibility, requirements to protect against natural disasters, and other design goals to help improve our quality of life, however, the impetus for building codes arose primarily out of the need for protection against fire. Some of the earliest versions of building codes were more focused on the protection of the building itself rather than the safety of its occupants. The earliest versions of building and fire codes were considered by some as merely documents with recommendations on how to make buildings safer, not the legally enforceable documents they are today. These codes were often dismissed by frugal or pretentious building owners, but this attitude resulted in a significant loss of life in what would become some of the most notorious fires that helped shape the building and fire codes of today.

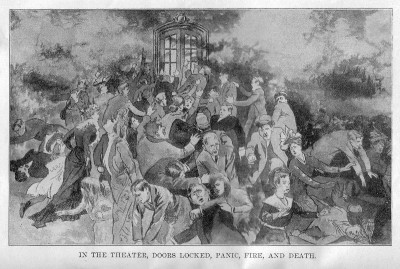

The Iroquois Theatre Fire

Chicago, Illinois – December 30, 1903

One cannot help but draw correlations to the storey of the Titanic when considering the Iroquois Theatre fire. Over a century later, the fire that broke out inside the then newly minted and “absolutely fireproof” Iroquois Theatre in Chicago still ranks as the deadliest single building fire in U.S. history. Rushing to finish the theatre to open for Christmas holidays, the owners and their hired fire warden ignored many of the fire safety deficiencies noted by the City’s fire captain. Municipal and regional fire chiefs did not have the same level of authority they have today to implement fire safety measures in buildings since many codes had not yet been enacted. The building was completed with no sprinkler system or fire alarm, poorly marked exits, an overabundance of combustible wood trim finishes, and fire extinguishers that proved to be useless. Perhaps more harmful than the lack of designed fire safety features (controlled today by building codes), it was measures taken by theatre staff and owners (guided today by fire codes) that were responsible for the 602 deaths. Awareness of the fire was relatively quick and the fire only lasted 20 minutes but because 27 of the 30 exit and egress doors were locked or blocked with curtains or metal accordion gates, two thirds of the patrons were trapped and unable to escape. The theatre was also well over capacity with standing room tickets sold to increase profits.

The events resulting from the fire would go on to inform some of our most trusted and referenced building and fire codes used today. With the lessons learned from the fire came new fire safety provisions including:

- limits on maximum seating capacity

- improved paths of egress

- exit markings along egress paths

- continuously lit exit signs

- emergency power for emergency lights and exit signs

- improvements to exit doors including the invention of panic bars

At this time in the evolution of building and fire codes, the act of forcing building owners to pay for costly life saving equipment and features was still considered a burden by many property owners but lawmakers and politicians were beginning to realize that the risk to lives was much too great to ignore.

Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

New York, New York – March 25, 1911

The Triangle Shirtwaist Company ran a textile factory that operated on the top three floors of a 10-storey building and employed about 500 workers, mostly immigrant women and young girls. Like many of the great building fires near the turn of the century, there were numerous factors in both building design and operational practices that contributed to the intensity of the fire and loss of life. Some of those were:

- no fire alarm to warn people on other floors

- insufficient number of stairs (2) for the size of floor area (+10,000 ft2)

- exits locked by owners to reduce theft and control the movements of employees

- inward swinging exit doors

- lack of fire drill training

- poorly designed exterior wall-mounted fire escape

- combustible wood floors, windows, and trim in a tall building

- overabundance of flammable cloth rags throughout the floors

As would be expected, once the fire broke out and reached a certain size, it became impossible to extinguish.

Like the Iroquois Theatre Fire, the Triangle Shirtwaist fire was pivotal in advancing fire safety provisions for buildings. This fire has arguably had the biggest impact on the development of one of fire prevention’s most important codes, NFPA 101 – Life Safety Code. The NFPA describes the Code as,

“the most widely used source for strategies to protect people based on building construction, protection, and occupancy features that minimize the effects of fire and related hazards. Unique in the field, it is the only document that covers life safety in both new and existing structures.”

It was the Triangle Shirtwaist fire that prompted the creation of NFPA’s Committee on Safety to Life which laid the groundwork for NFPA 101, still referenced by thousands of fire prevention professionals today. The following year the NFPA published a pamphlet titled “Exit Drills in Factories, Schools, Department Stores, and Theatres” which was the first publication produced by the NFPA’s Committee on Safety to Life. The pamphlet, along with others published by the Committee, went on to form the basis of the NFPA’s Building Exits Code released in 1927. This was later rebranded as NFPA 101 – Life Safety Code. The Canadian National Building Code and Fire Code both reference this code as well as many more NFPA standards and codes. All these documents have contributed to the codes we use in Canada to mitigate harm to humans and buildings from fire.

Some of the code changes that ensued after the Triangle Shirtwaist fire were:

- higher construction standards and more restrictions for fire escapes

- mandatory fire drill training

- improved exiting from high-rises

- sprinkler systems

Cocoanut Grove Fire

Boston, Massachusetts – November 28, 1942

As noted in the opening paragraph, codes are living, evolving documents that grow into maturity as our knowledge base and experiences with fires broaden. No two fires are exactly alike and there are unique lessons to be learned from every one. Apparently, the owner of the Cocoanut Grove nightclub and the fire chief who inspected it just ten days before the fire had not learned from previous fires. Many of the same fire risks and behaviours by the staff contributed to the notorious Cocoanut Grove fire which claimed 492 lives and injured another 130. The real tragedy of Cocoanut Grove is that they had the hindsight of previous fires with established codes and best practices for preventing fire and saving lives. They also had much more advanced fire protection technologies available to them. Sadly, as time passes, people become complacent and forget the lessons learned from previous disasters.

As in the Iroquois Theatre and Triangle Shirtwaist fires, exit doors were blocked, the ones that were not blocked swung inwards, and the club was filled with flammable finishes and decorations. A unique feature of Cocoanut Grove was a large revolving door used as the main entry and exit. This proved to be horribly ineffective for hundreds of people in a panicked state. About 200 people were trapped behind the revolving door as it became jammed with people clambering overtop of each other trying to escape. The blaze that started in the basement spread rapidly and lasted a mere twelve minutes but even with a slower spreading fire, the absence of emergency lighting, lack of venting to allow smoke to escape, and inadequate exiting would contribute all the same to a lethal situation.

Many of the code provisions designed to save lives were already well established when the Cocoanut Grove nightclub burned, although some of them underwent revisions or improvements and some new ones were added. Some of them were:

- collapsible panels on revolving doors or provide at least one adjacent normal outswing door

- restrictions on combustibility of construction materials

- limitations on flammability of interior finishes and furnishings

- emergency lighting

The new restrictions on interior finishes resulting from Cocoanut Grove were very general in nature with no standard of measurement for combustibility. Advances in this field eventually led to the development of the Steiner Tunnel Test by Albert J. Steiner of Underwriters Laboratories which is still used today to test for combustibility in some of the standards referenced in the National Building Code like CAN/ULC S-102 Surface Burning Characteristics of Building Materials and Assemblies. Another lasting and significant impact of the fire was that virtually all the hazards at Cocoanut Grove were incorporated into the NFPA’s Building Exits Code and that the Code was adopted by many more jurisdictions across the United States, due in large part to the efforts of the fire service. The awareness and appreciation for the importance of fire prevention and safety in buildings seemed to be finally taking hold but there were still many more lessons to be learned.

Our Lady of the Angels School Fire

Chicago, Illinois – December 1, 1958

The Iroquois Theatre fire led to safety improvements for theatres and similar assembly occupancies. The Triangle Shirtwaist fire became the catalyst for stronger labour unions who fought for safer working conditions in factories and industrial buildings. The Cocoanut Grove fire led to sweeping changes in fire safety for nightclubs and restaurants. Sadly, it would take a similar calamitous event for changes to affect schools. Our Lady of the Angels was a catholic school in Chicago ravaged by a fire that resulted in 93 fatalities – 90 pupils and 3 nuns. Again, the main culprits responsible for the fatalities were the usual suspects.

- inadequate exit facilities

- too many combustible interior finishes

- no sprinkler system

- no fire alarm

- lack of fire separation between the classrooms and hallways

It is important to note that due to a grandfather clause, the Our Lady of the Angels School did not have to comply with all the new fire codes and standards that newly constructed schools at the time were required to adhere to. Similarly, the National Building Code includes a note, A-1.1.1.1.(1) Application to Existing Buildings that states,

“It is not intended that the NBC be used to enforce the retrospective application of new requirements to existing buildings or existing portions of relocated buildings, unless specifically required by local regulations or bylaws.”

The difference in this grandfather clause of the 1950’s and of today is that there is more acceptance towards a higher standard of safety in buildings compared to past decades. The note goes on to say,

“…it is the intent of the CCBFC that the NFC not be applied in this manner to these buildings unless the authority having jurisdiction has determined that there is an inherent threat to occupant safety and has issued an order to eliminate the unsafe condition.”

Code changes and school fire safety regulations were overhauled to create safer learning environments for students. In the United States over 1,000 schools were re-inspected for compliance with the new standards. Some of those changes were:

- requirement for fire alarms in all schools

- automatic sprinkler systems

- self-closing exit doors opening outward

- fire rated doors at exit stairwells

- maximum heights for egress windows

- fire separations and fire-resistance ratings

- dedicated emergency lighting

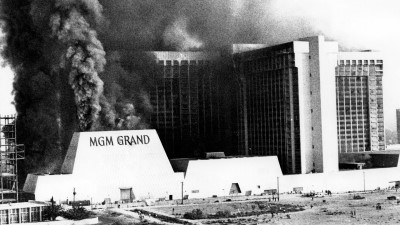

MGM Grand Hotel & Casino

Las Vegas, Nevada – November 21, 1980

Hotels are another building type that have a long-established history of notable fires that influenced the development of building and fire codes, not just in Canada and the U.S., but all over the world. A well publicized and investigated fire in more recent times is the one that happened at the MGM Grand Hotel in Las Vegas. It is amazing to think that even in the 1980’s, a 26-storey building with about 2,000 hotel rooms and a capacity of over 5,000 could exist without a full sprinkler system.

A local building inspector granted the sprinkler exemption despite opposition by fire marshals. It turned out to be a fatal mistake that resulted in 85 deaths. There were other major contributing factors to the deaths however, the main one being smoke inhalation. Of the 85 that died, only one person was reported to have died from burns alone. Nearly all casualties had succumbed to smoke inhalation and carbon monoxide poisoning, most of them on the upper floors of the hotel.

The MGM Grand fire illustrated that smoke can be just as deadly as the fire itself. The fire was confined to the first floor only and some areas on the first floor that were sprinklered did not experience significant fire damage. The casino and restaurant lacked sprinklers and allowed the fire to spread quickly, burning all types of flammable furnishings, fixtures, and finishes creating toxic clouds of smoke that traveled up elevator shafts and throughout the hotel. The distribution of smoke to hotel rooms was aided by a ventilation system that continued to operate despite the fire.

After the fire it became clear that stopping the spread of noxious gases and smoke was as important as containing the spread of fire. New code provisions were introduced to address the risks to safety witnessed at MGM Grand. Some of them were:

- mandatory sprinkler systems in buildings of a certain size or number of stories

- smoke detectors in rooms and elevators

- exit maps posted in all hotel rooms

- provisions to limit the movement and spread of smoke

Articles 3.2.4.12. Prevention of Smoke Circulation and 3.2.6.2. Limits to Smoke Movement are two areas of the NBC that address many of the problems encountered during the MGM Grand fire.

Summary

The five fires discussed in this article are all deeply tragic, but they have also all contributed positively to the development of Building and Fire Codes, helping to make buildings safer for future generations. With over a century of recorded and detailed knowledge on thousands of fires, firefighters, fire chiefs, fire investigation specialists, architects, and engineers are all still learning how to use their combined knowledge to make buildings safer. We have made huge leaps since earlier days when entire towns or cities could be consumed by flames in a matter of hours or even minutes. We are making progress and our buildings are becoming safer, but we have a long way to go before firefighting becomes a sunset occupation.

4 Responses

Thanks for taking the time to put this summary together Nelson. As you point out, it is easy to get complacent over time and take for granted the safety that our modern codes provide in new buildings. It is always a good reminder to read these tragic case studies.

hello! any major fires in Florida that lead to creating a fire code?

Hi Yaisy. Not that I know of but Google is pretty good at digging up information like that. Sorry I couldn’t be of more help.

This is great. As an American, the post-Uvalde “solution” of the political Right of limiting all means of egress to a single door may be what finally gives me a stroke.