The intent for the ‘Beyond the Codes’ series is to raise some awareness around important issues that go beyond the current codes. When there is enough voice and demand to ‘codify’ some of these issues, only then can we raise the bar for minimum requirements.

Part 2 is dedicated to accessibility and inclusivity as it applies to buildings. The building code has minimum requirements…but they are just that – minimum.

Problems with the Current Codes

The building codes are not perfect documents and some requirements seem inconsistent, aren’t worded clearly, or just don’t seem caught up to current times. Working for a municipality as a plan reviewer and now as a code consultant, I have found it is quite rare for a design to meet minimum code the first go around. Why is that? Part of the problem is that the code tends to jump around and lacks graphical references, and details just get missed. There are some handbooks and guides out there, but the ones I typically reference have not been updated for the new editions of the codes.

The British Columbia and Vancouver codes require areas to be accessible ‘where work functions can reasonably be expected to be performed by a persons with disabilities’ in. Who makes the call of what is reasonable? When reviewing warehouse applications, I have been told that ‘someone with a disability could not work here’…. to which I let them know that my step-brother is a paraplegic and operates a loader. On the positive side, this wording does not exist in the National code, and as such there are very few locations where accessibility requirements are not required. I’m not sure of the specific intent behind adding the ‘reasonably be expected’ wording in…but I do know that it is applied differently depending on where your project is and can result in buildings that miss the mark for inclusivity.

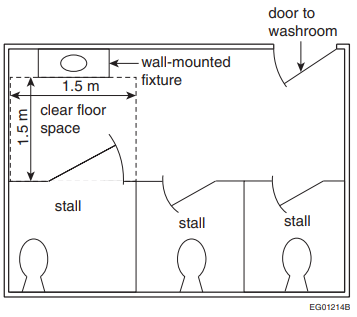

Another problem is the use of the wording ‘clear space’ in various requirements. The Notes to the code don’t help either. Sometimes the ‘clear space’ is shown slightly impeding on a fixture, where in other examples it is not (see images below). I’ve always taken the stance that ‘clear’ means ‘clear’…which is not always the answer people want to hear when trying to save on space. I’ve never personally had to navigate a washroom with a mobility device, so I don’t feel it is appropriate for me to make the call of how much impeding on clear space is okay. The codes do allow CSA B651 to be used for certain requirements which provides more clarity around clear space… but it is a different set of standards and needs to be used as a whole if desired.

Progressive Canadian Codes

I’ve been working with the Vancouver code for the last year, and am impressed by considerations they give to increased accessibility and inclusivity. Some of the additional requirements are:

- Every new dwelling unit constructed must meet adaptable requirements. Adaptable design allows for accessibility features to be added easily in the future, so that occupants can ‘age-in-place’. This includes such things as wider doorways and extra reinforcement to allow for future grab bars. Check the Vancouver requirements out in Subsection 3.8.5. The BC building code also has adaptable requirements, however it is up to each jurisdiction to adopt if, and to what extent, these are required.

- Most new apartment and condominium buildings are subject to Enhanced Accessibility requirements. This includes such things as gender neutral washrooms and power door operators where not normally required. Check out the full requirements in Sentence 3.8.3.1.(2).

- Enhanced security in parkades to increase safety and sense of security. This includes increased lighting levels and required glazing to see into a stairwell vestibule before entering it. Read all the requirements for increased building security in Subsection 3.3.7.

- Universal washrooms are required in every new building, which are inclusive for persons with disabilities, families, and transgender and non-binary people. Universal washroom requirements are found in Article 3.8.3.12., and a best practice guide for Strategies for Universal Washrooms and Changerooms in Community and Recreation Facilities has been provided by HCMA for those who want more guidance.

How can we do better as code consultants and design professionals?

Well, I think it starts with acknowledging that the code is truly the minimum, and is actually not that great when it comes to inclusive design. Here are a few of our ideas, and we’re interested to hear what others think.

- Can we provide a reduced rate for projects that go above and beyond in terms of universal design?

- Can we learn about architecture and development groups that are openly supportive of accessibility and inclusion? Can we choose partners that align with our values…by their actions and not just their statements?

- Can we take the time to include community groups in proposed designs, to get feedback on how we can make them more inclusive?

Just because progressive design is not ‘codified’ doesn’t mean that we can’t share what we know. As a code consultant I’ll often slip in comments that encourage more universal design and preface it with “although not required by code, best practice would be to…”. Even if the suggestion isn’t incorporated into that design, sharing the comment increases awareness.

Honestly, if my my late father-in-law and step-brother were not bound to wheelchairs, I may not be as aware of the impact that universal design has. Awareness really is the first part of meaningful change. Even if you are not directly impacted, I challenge you to start questioning on how you can do better.

How can we do better as architects?

We are not architects, but have worked with some wonderful firms who are committed to universal design. HCMA is one of them. Check out their Strategies for Universal Washrooms and Changerooms in Community and Recreation Facilities guide and their Managing Principal Darryl Condon’s recap of their journey over the last 20 years towards inclusive design in the video below. As Darryl states, diversity is what you have and inclusion is what you do about it.

Diversity is what you have.

Inclusion is what you do about it.

How can we do better as developers?

We are not developers, but have worked with many and have seen a wide range of priorities. Developers have so much opportunity to put people first.

A cost comparison feasibility study released from HCMA on behalf of the Rick Hansen Foundation (RHF) was completed and results published earlier this year. Care of the HCMA website, the results showed that:

- When projects meet the requirements of building codes alone, they’re unlikely to provide meaningful access for people with disabilities, or allow them to participate fully, or with dignity.

- New projects can achieve the RHF Accessibility Certification at no additional cost. It just requires thoughtful design, which could be as simple as materials selection, colour contrast and signage, and the positioning of controls, hooks, and mirrors.

- To go a step beyond, projects can reach RHF Accessibility Certification Gold (the highest rating) for an average construction cost increase of just 1%.

You can read the full report here.

Thanks for reading along. The changes we make today can have such an impact. We are part of creating the built environment, so let’s make sure it works for all people.

If you missed Part 1- Black Lives Matter of the series, you can read it here.

6 Responses